Don’t get too excited. It’s a bar. A tavern in the middle of Ashland. Right, that one, the one in Oregon where they have the Shakespeare Festival. I’m on a journey of “uncovery” after a year of recovery from various ailments, the most important being two knee replacements. . . don’t get too concerned, there are only two, so, done with those.

Uncovery is a better term for me because I find the world to be a bit like an onion, tasty in all sorts of things; hamburgers, pico de gallo, in a bowl of menudo. Chopped or sliced, the world is like a condiment or an ingredient for a soup or, you know, grilled.

The uncovery bit is, well, have you ever been to a grocery store to find an onion and discovered that they all seem to have these seemingly endless layers of paper thin skins? Where you have to peel them off one by one till you get the white or red or yellow? And, even then, you start to cut into it so you can do your best to bring out flavor and, damn, if there isn’t one more layer that’s still sort of tough and stretchy. You can add it to whatever you’re making but it doesn’t really have that much crunch. It’s like a faux fruit that really should be discarded and then you can get a feel and flavor of savory water-filled layers. Satisfying in those burgers, pico, or menudo (yeah, I know some of y’all are wretching a bit about the menudo, but, hey! This is my palate, so go with me).

Yes, the world is just like that, an onion. A lot of dated layers covering what is most salient about it. The onion and the world. At least for this post.

I’m back on the road sitting on a Sunday afternoon in a bar called Oberon’s Three Penny Tavern. I’ve been in Ashland for a few days, took in a great show,”Virgins and Villains”, about a woman’s self biography set in the roles she played in Shakespeare’s plays, I climbed onto the Mountain of the Rogue, a hiking trail looking over the Rogue River, walked along the River, and interspersed among the scripted lines of women in the Bard’s plays, walked the town, its parks, and became a local at Oberon’s. For a few days.

This time has been a layer, a savory onion layer, full and moist, enjoyed as a complement to a journey I have just begun, rich in a flow of history and the stories you uncover.

You see, a world stacked with layers, stories covering other stories, covering other stories, has a way of covering important truths–That before the world began to hurt, before we’ve come to this vicegrip notion that there is no way out of our dilemmas except through war and revolution, there was a time where we could change the world by three simple freedoms. We could disobey, we could walk away, or we could re-create a different way.

I am traveling the Western continental United States in a small car packed with my essentials, snacks, clothes, pillows (right, to me, sleeping is a yin restoration exercise propped with pillows) and my phone with subscriptions to Spotify and Audible Books. My most favorite part of driving is listening to works that take me through the journey.

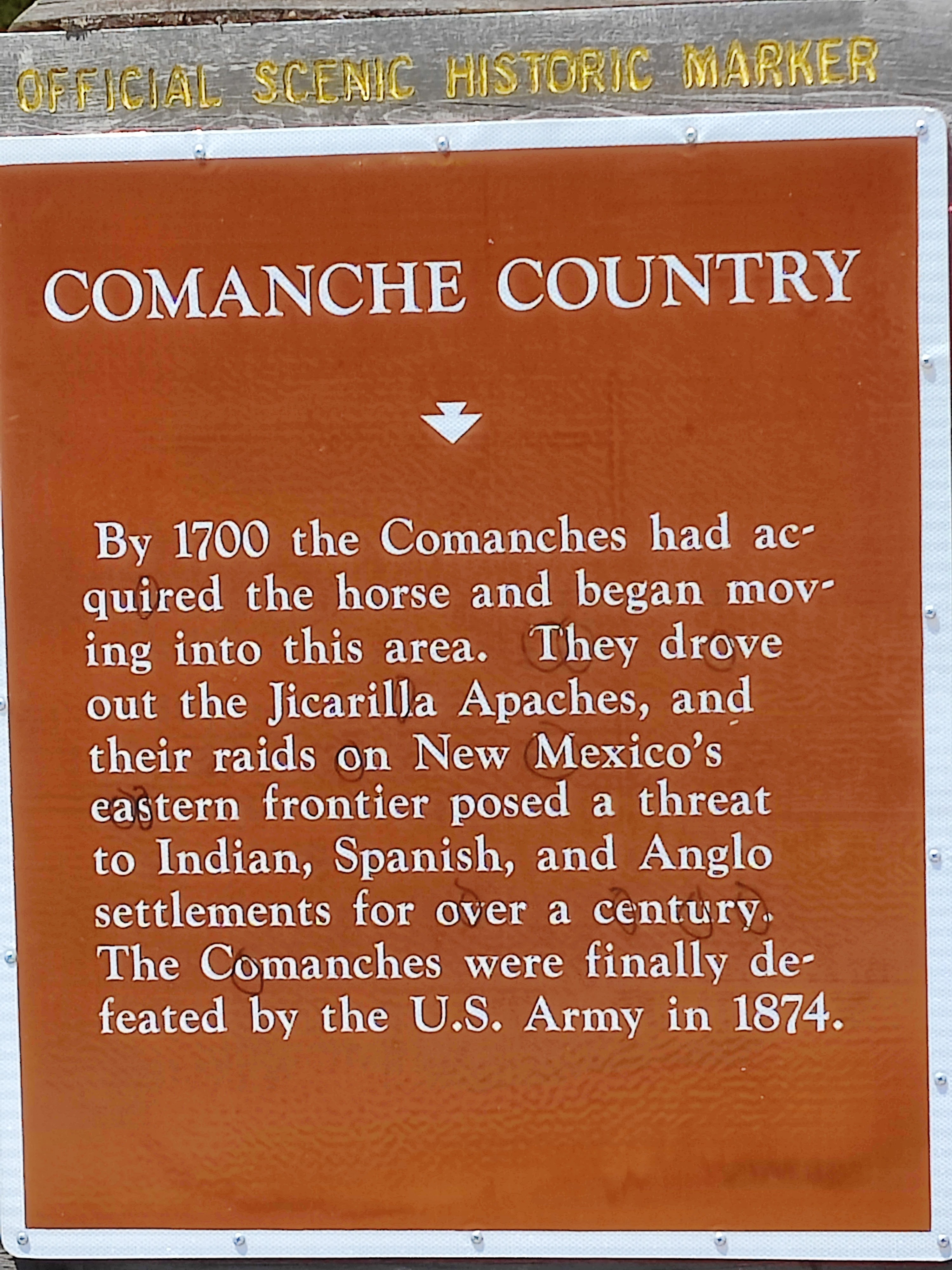

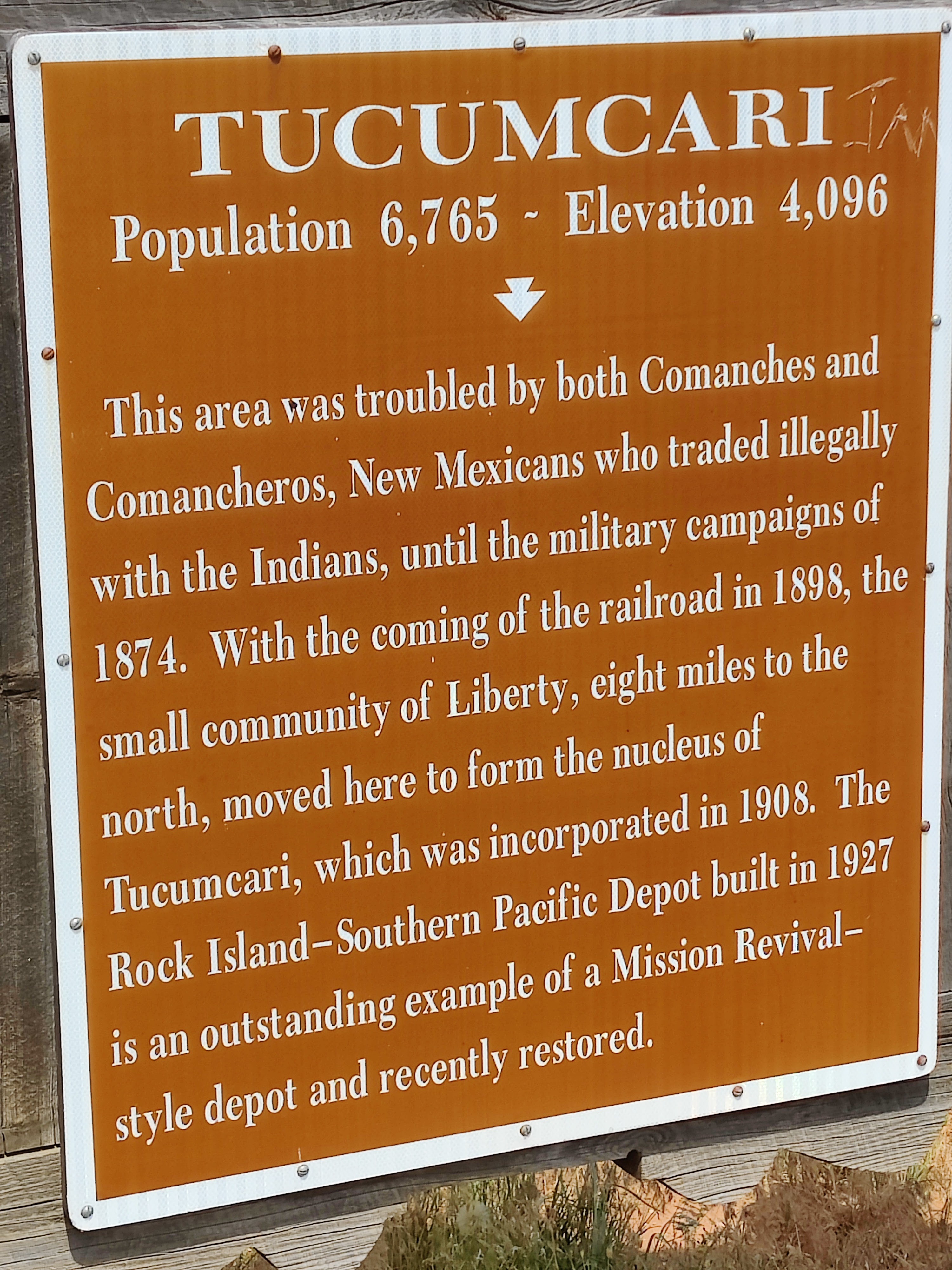

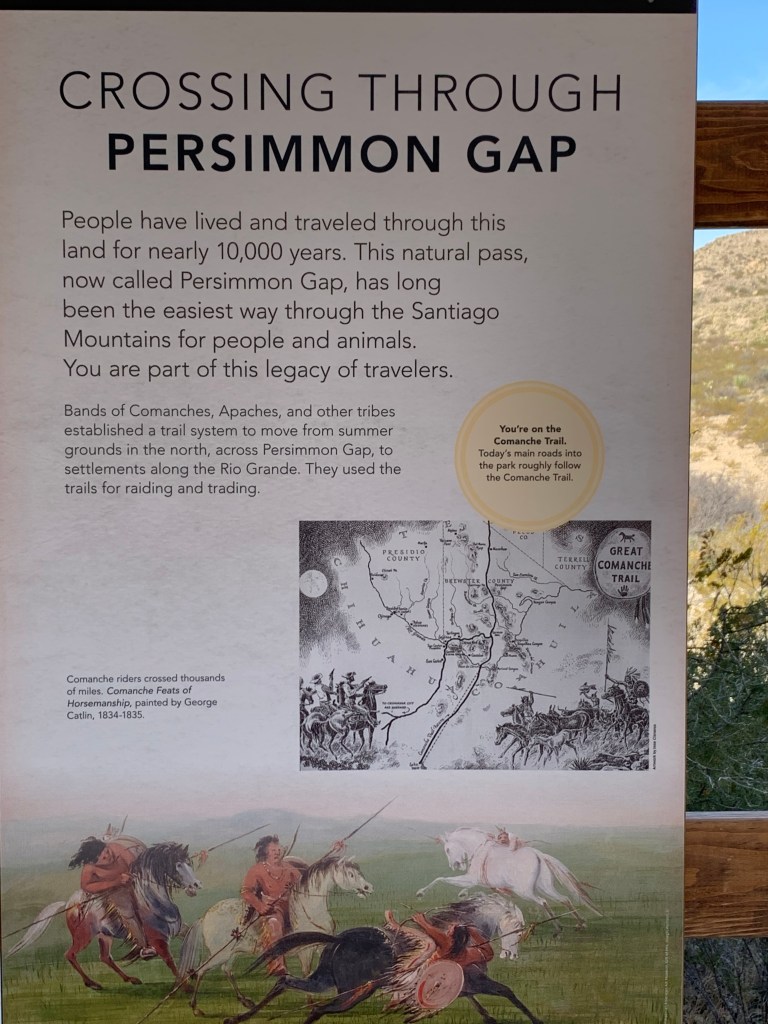

One such book is “The Dawn of Everything” written by an anthropologist, David Graeber, and archeologist, David Wengrow. As I’ve been traveling, the books I’ve listened/read complement the feelings, the sights, the parts I visit that are the story of the world. In their book, these authors counter the narrative that civilization has been a stairstep toward progress, a linear movement from primitivism to civilization. Their uncovering of the layers history showed how that for much of early periods of history, humans lived less centralized, less imperial forms of societies and that, even when such imperial societies presented, they often were rejected by large numbers of people engaging in what the authors describe as three basic forms of freedom; the freedom to escape our surroundings, walk away, the freedom to disobey authority perceived as arbitrary, and the freedom to reimagine and remake society in a different way.

In many instances, historians describe when people did such things as societal collapse, “dark ages”, the downfall of empires. In truth, or at least in evidence, societies that moved away (sometimes literally) from empires enjoyed periods of peace and decentralized forms of rule, what some may consider more participatory forms of democracy.

I thought of that as I watched a lovely young girl, daughter of a photographer shooting photos of the banjo player playing that Sunday afternoon (yes, I’ve moved on from Ashland, you can only hold down a bar stool and glass of mead for so long). People going about their lives (relatively) free to enjoy a drink, hear a banjo, watch a child dancing free. I wonder what would happen if enough people simply stopped going along with militarism or the expectation that we should “be productive” and only “play hard” after “working hard”?

The expansion of national empires has made it difficult for people to walk away from oppressive surroundings, I think this one reality, embodied by the disdain for immigrants present so ubiquitously may be the biggest constraint impeding our ability to “vote with our feet”. There are borders and razor wire, not to mention racialized animosity for people seeking to escape violent conditions.

I read (listened to) this book and one other as I left Minnesota earlier this May. So much of what I’ve seen resonates with what I’ve read/heard.

Layers

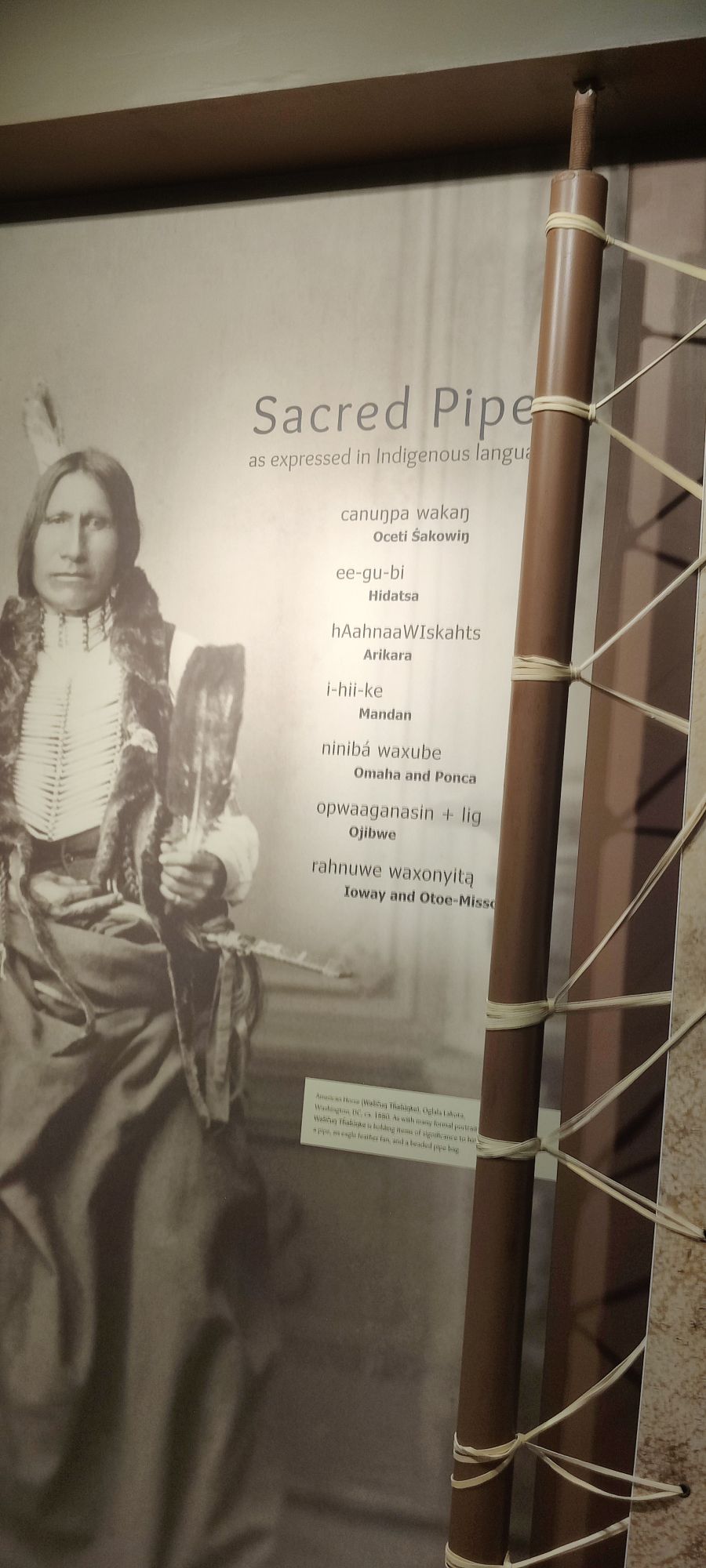

Layers. There’s a town in Southern Minnesota called Pipestone. Yes, Pipestone is exactly what you think, stone that you can make pipes. To smoke, haven’t heard it would be useful for plumbing, but, hey. Maybe?

The thing about pipestone is that it doesn’t seem to have many uses, except for putting stuff into it and smoking it. Archeaological evidence shows that people in what is now Pipestone County, Minnesota have been quarrying pipestone from over 3,000 years before the present.

Thing is, pipestone only shows up in the geologic stratigraphy sandwiched in between hard rocks of quartzite–called “Sioux quartzite”–and other hardened sedimentary sandstones. So, in between layers. Early peoples did a lot of hunting and gathering, needing hard stones like quartzite to make tools such as arrowheads and spear points, maybe other tools. But, so, how did they decide on pipestone? And, what led them to realize it would be a useful material to make smoking pipes?

I know what you’re thinking. . . well, I don’t know, but I want you to think so I can make this observation. Smoking a pipe is a cultural practice. So, in order for some . . .one to decide that what we now call pipestone was a good idea for making pipes and taking whatever we want to put in it and smoke it, somebody a) had to make a culture, b) decide it was cultural to smoke a pipe for various reasons having to do with inter and intracultural methods for mediating conflicts, or, you know, just shooting the breeze.

What possessed people to do any of that? I suggest that there is a simple, which is to say, a rather complex explanation that begins with women, and, well, ends with women. Or, rather, layers.

Another book that has informed my thinking about layers, culture, and how somebody decided to use pipestone to put whatever it was they want in it and then smoke it, thereby creating that honored non-profane saying “put that in your pipe and smoke it”, is a work by Chris Knight, Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture. In that work, Knight produces evidence for how some of the most basic cultural frameworks for much of what we call civilization began with women and their need to create space, and time, to give birth to and care for children. Knight, much like me, wanted to know just how did we get around to creating, as opposed to making, time? What possessed “us” to set a proverbial timer on everything from precision clocks to making a “fashonably late” entrance to a soirée.

In short, women needed men to hunt and bring meat to a set place so that women could concentrate on having and bringing up children. Women learned, discovered, uncovered that they could synchronize menstrual periods and periods of fertility thereby being able to engage in a “sex strike” giving advantage to men who could learn that their lineage of procreation would proceed if they followed suit and honored this strike, as well, of course, other women. Over “time” (sic) women realized that such syncronization was ideal to be made in conjunction with phases of the moon, hence, menstrual. Starting this whole process of course (well, at least seems right to me) required a whole set of practices, expectations, in short again, culture, to make all this kind of thing work. Men, being relegated to hunting and perhaps later, agronomy (largely under the influence of women and their primarily foraging, cultivating practices), learned (discovered, uncovered) that should they go along with this idea of culture, their line of succession, well, more specifically, their ability to get sex, was dependent on going along, to, you know, get along, and get it on. Those women and men who followed were the ones to “win” because they successfully had more and consistent offspring. Those who didn’t. Well, they didn’t get a chance to put things in their pipe and smoke it.

Yes, I know, it’s a bit much to go into explaining about learning, discovering, uncovering layers of rock to arrive at a) discovering pipestone, b) turning it into pipes, and c) being able to make use of it for ceremonial, cultural, practices of intercultural connection, cooperation, conflict resolution, and shooting the breeze.

But, yes, but, none of that discovery, uncovery, learning happens without culture, and culture doesn’t happen without a reason. Fredeick Douglass once observed “power concedes nothing without a demand”. I submit that it began with women understanding their power by recognizing the utility of a life based in nurturing, requiring the base needs that necessitated buiding culture, in the only way that men could understand; conceding nothing without a demand, that if you want pleasure and want to continue, you will only do so by providing meat and waiting, biding time.

Of course, all of that is how we tend to think about such intersexual relations. It isn’t very relevant as we get older and retire, which is why women, and men, of a certain age have to overcome this “procreational urge” in guiding our interactions with each other. . .I think that may be too much information. But, hey, made you look!

Layers, the world has them, we have them.

I’ve been pursuing the need to understand the layers that made us, got us here, and, I hope will take us to a better place. Graeber and Wengrove observe in their book that the times we put our destinies in less oppressive hands were when we thrived. And the ways we did so, were in large part the work of women leading progress. The world before it began to hurt. I think we will get to a less hurtful world if we do just that; put the rights of women at their proper place and role, to guide us out of this largely “man-made” dilemma of existence where we have endangered ourselves and the entire planet.

Maybe it will be in time. I hope so. But it will require us to understand the layers that we have and how we can peel them away enough to enjoy a life ultimately complemented by the best layers of our nature.

In short, we are best when we can reveal those moist, juicy layers of ourselves and savor them as we build a better life.

So, see? We’re all just a bunch of really fresh onions ready to be enjoyed. If we take the time to peel away the less than useful layers.